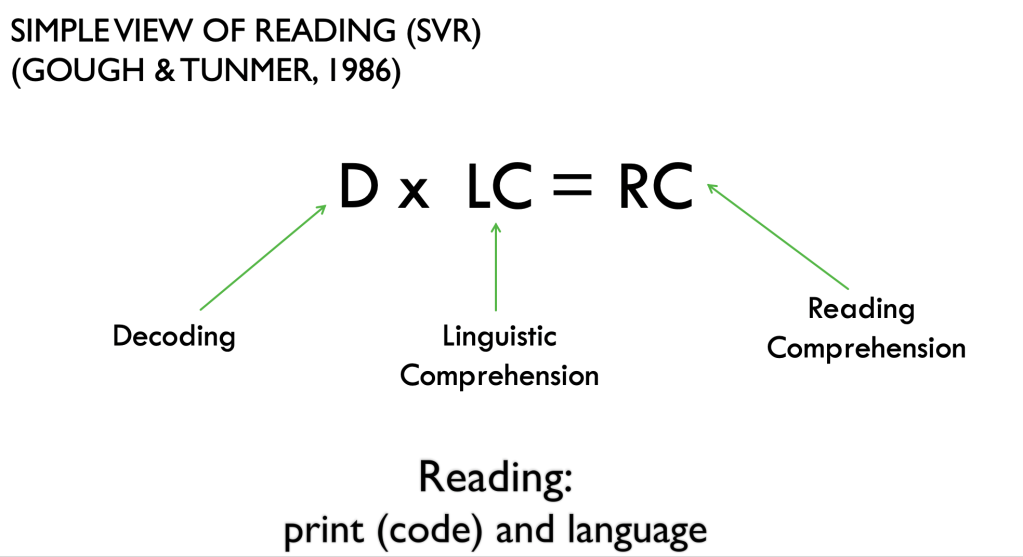

The Simple View of Reading was first proposed by Gough and Tunmer in 1986 and is one of the most supported models of reading to date. The gist of the Simple View is that Reading Comprehension (RC) is the product of Decoding (D) and Linguistic (or Language) Comprehension (LC).

RC is the *product* of D and LC because if either decoding or language comprehension equals zero, the end result (reading comprehension) is zero. For example, if I can decode Spanish (pronouncing the words on the page accurately) but don’t understand a word of it, I won’t comprehend it. And, if a child can understand simple spoken English (my 2 year old) but can’t decode printed words on the page stating the same, she won’t have any reading comprehension (because she can’t read yet).

This theory, now supported by decades of empirical research, is the basis for how we can understand reading development, instruction, and assessment. Sometimes, a lack of training in the Simple View causes well-meaning professionals to conflate decoding with comprehension at the expense of valuable instructional time.

This is sometimes seen in the field when we ask students, who have yet to learn the code, to “read for meaning” in kindergarten; predictable books are given to students sitting around a kidney shaped table so they can “read” them based on the pattern and the pictures. This misconception is also seen when professionals state that sounding out words can “get in the way of making meaning.” More accurately, decoding is the way kids *access the language* underneath the printed text (or code).

A child entering kindergarten already knows what a horse, a cow, and a sheep look like; however, a common predictable book, “I see the animals,” may read, “I see the horse. I see the sheep. I see the cow. I see the animals!”

An objective this teacher has for the students may be for the them to make meaning from the printed words. Actually, the exposure to rich content, syntax, and vocabulary that young students need could be coming from teacher read alouds. The decoding instruction kids at this stage need should instead focus on the simple letter-sound correspondences they have been explicitly taught (phonics).

Given predictable texts, some children, who have good phonemic awareness skills and letter-sound correspondences already, may implicitly pick up on patterns within the English orthography (written language system) on their own while they read these predictable books; they may teach themselves to read (see Share’s self-teaching hypothesis). Other children, who enter school with underdeveloped phonemic awareness skills, will just fall further and further behind in these systems.

With predictable texts, the teacher is actually teaching the child the English orthography must be either memorized (hello, “sight words!”—another post for another day) or guessed based on the context and the first letter(s). With predictable texts, the teacher is implicitly teaching the child the English orthography is *unpredictable.*

However, in reality, we want children to learn that English is an orthography that can be decoded, or sounded out. Although it is a deep, opaque orthography, it is highly regular. We can systematically instruct students in:

- letter-sound correspondences (i.e., how graphemes, or groups of letters that make one sound—ch, dge, igh, f—relate to phonemes, or the smallest sound that makes a difference in the word’s meaning—/ch/, /k/, /sh/; /j/; /ī/; /f/),

- phonics patterns (the bossy e that makes the vowel long, as in hike or brave, or using “tch” after a single, short vowel, as in hatch or pitch),

- phonetically irregular words, specifically pointing out which part of the word is phonetically irregular (s[ai]d, t[w]o, [o]nce)

- syllable types and division strategies (open syllable—the vowel is long—he, go, [pi]lot, or closed syllable—the vowel is short—cat, flop, [bub]ble, among others),

- morphology (the smallest units of meaning within a word—construct, structure, instruction), and

- etymology (how words originate, change, and relate to each other—twice, two, twin).

We can teach these skills and principles explicitly to all children—the photo below was from a couple of advanced students in a PreK classroom. It is helpful to all, harmful to none, and essential for some.

That is why it is so important to understand the Simple View before choosing an intervention… is the child struggling with the code (D), is the child struggling with the language (LC), or both? And why it is important to ensure a strong Tier 1 (general education) curriculum that includes explicitly teaching the printed code to build students’ decoding skills and includes rich content knowledge, vocabulary, and syntax to build students’ language skills.

Hollis Scarborough’s Reading Rope (2001) gives us more insight into the complex ideas the Simple View of Reading seamlessly represents. In the image below, the top (red) strands represent a student’s language comprehension (LC) development. The bottom (blue) strands represent the components within a student’s word recognition development (D).

As the student’s word recognition becomes increasingly automatic and language comprehension becomes increasingly strategic, skilled reading emerges.

Considering the typical deficit of a student with word-level reading difficulties lies in phonemic awareness skills, this graphic may shed light on the many components playing a role in reading the words on the page. Students with significant difficulties in word-level reading skills despite adequate instruction may have dyslexia (a specific learning disability in basic reading skills).

Students might also be able “break the code” and pronounce all of the words on the page, but have trouble understanding what they are reading. These students may have deficits in syntax (grammar), vocabulary, or content knowledge. Students who have significant difficulties with language comprehension despite adequate instruction may have DLD (Developmental Language Disorder).

All of these skills exist on a continuum, as shown in the graph above. Understanding the complexities of the Simple View of Reading can help us organize our thinking and may lead to more valid assessments, targeted lessons, and intensified interventions.

- For more information on Dyslexia, see this post.

- For more information on DLD, check out this podcast by Dr. Tiffany Hogan and this intro video on DLD.

I accept all your findings to be right on. I taught Kindergarten and Grades 1-2 for 39 years so I understand what you are saying.

LikeLike

I’m glad you can see this apply to your practice!

LikeLike

What do you suggest for Gr 3-4 homework for improving reading comprehension?

LikeLike

Going back to the model, are the student’s deficits in decoding or language comprehension (or both)? Are the parents asking what they can do with students at home?

LikeLike

Thank you so much Tiffany for such an insightful article and also the research-based information. Being an SSP – Systematic Synthetic Phonics Teacher and Trainer; I am always looking for the latest papers or articles about the science of reading & writing to include in my training. I will surely mention what you have written and direct my trainees or any English Fellow Teachers to read you. Keep up!!! Looking forward to reading more of you.

Danielle – Language Mood English Club

LikeLike

Thanks for the thoughts and encouragement. Glad you find it useful!

LikeLike

Hi Tiffany

This is a great explanation. Easy to read and access. I have read so much lately on the simple view and reading role- you have done it absolute justice! Thanks so much!

LikeLike

Thanks for the feedback!

LikeLike

This is a pretty rad post. I’m sure my colleagues will prefer your succinct & readable explanation and application to me passing out a stack of Gough & Tunmer 😂

LikeLike

Haha! You can always give them the article as a follow up if they are looking for a good bedtime read 😉

LikeLike

How do you help those students who have poor language comprehension and poor decoding skills? Grades K-4

LikeLike

These students would require more time in intensive intervention. You’d need to evaluate their specific areas of need (phonemic awareness, phonics, syntax, vocabulary, background knowledge, etc) and provide targeted intervention to each area of need.

LikeLike

Wonderful summary of what everyone who works with kids needs to know. Also- easy to read and accessible for those unfamiliar with educational research. Printing for my clients!

LikeLike

Thank you! Glad you find it helpful and it is getting out into the world!

LikeLike

Tiffany, Thank you so much for your clear and concise article. I am working on bringing structured literacy to my district, instead of a 3 cueing system program and assessment, and I need this kind of article to give to my superintendent. Thank you!

LikeLike

Glad that you find it helpful!

LikeLike

Hi! Please continue to write more. I’ve found our twitter and facebooks posts incredibly clear and informative. I look forward the updates your future blogs.

LikeLike

Thanks! I’m glad you’ve found them helpful.

LikeLike

I like the comparison to an equation using 0. It provides a good visual. I am wondering how much phonetic teaching/basics will occur at the 4th/5th grade level.

LikeLike

Great question! Depends on student need, hopefully! If students can accurately decode and encode (spell) words, most of the instruction in reading will best be spent on the “LC” part of the equation. This can include instruction in morphemes (to understand word meanings), vocabulary, text structures, content knowledge, and grammar, among others. The equation doesn’t mean that each grade in school will give the same emphasis to the D and LC, but it is suggesting instead that students need to be proficient in both in order to be proficient at reading comprehension.

LikeLike

Can you please email a copy of the article with graphics to me? I’d like to use the article with teacher and leader groups; unfortunately, any way I try to print, some of the text gets blocked by the “WordPress” ribbon at the top. Thanks so much!

LikeLike

No problem! Glad it is useful. You can find a pdf version here: https://tinyurl.com/ss3uxba

LikeLike

This type of post with these subjects should be addressed more! They are extremely useful for society. Congratulations for the content

LikeLike

Glad it is helpful!

LikeLike

Today’s PD is on the simple view of reading and the implications for SDI in the elementary resource room.

LikeLike

I enjoyed reading this article, I hope that the schools make more educational trips to the public libraries and encourage the students to get the library card and increase the reading competitions as the children love a challenge, so when the teachers make reading into more a competition, it will be more fun and exciting time.

LikeLike