You may have heard of Dr. Ehri’s theory of orthographic mapping, or the glueing of phonemes to graphemes within words so that the written word is automatically linked to pronunciation and meaning. This process can involve mapping sounds to print in both phonetically regular words, such as kick (/k/=k, /ĭ/=i, /k/=ck) and words with what we think of as phonetically irregular parts, such as said (/s/=s, /ĕ/=ai, /d/=d). This process is also said to account for glueing or mapping chunks of words (for example, re- or -ture) to sound as well, allowing students to recognize parts of longer multisyllabic words.

You may have also heard of Ehri’s Phases of Sight Word Learning, a kind of roadmap on which students travel down in their journey of learning to decode words. Here is a piece by UFLI explaining Ehri’s phases if you can’t access the article above.

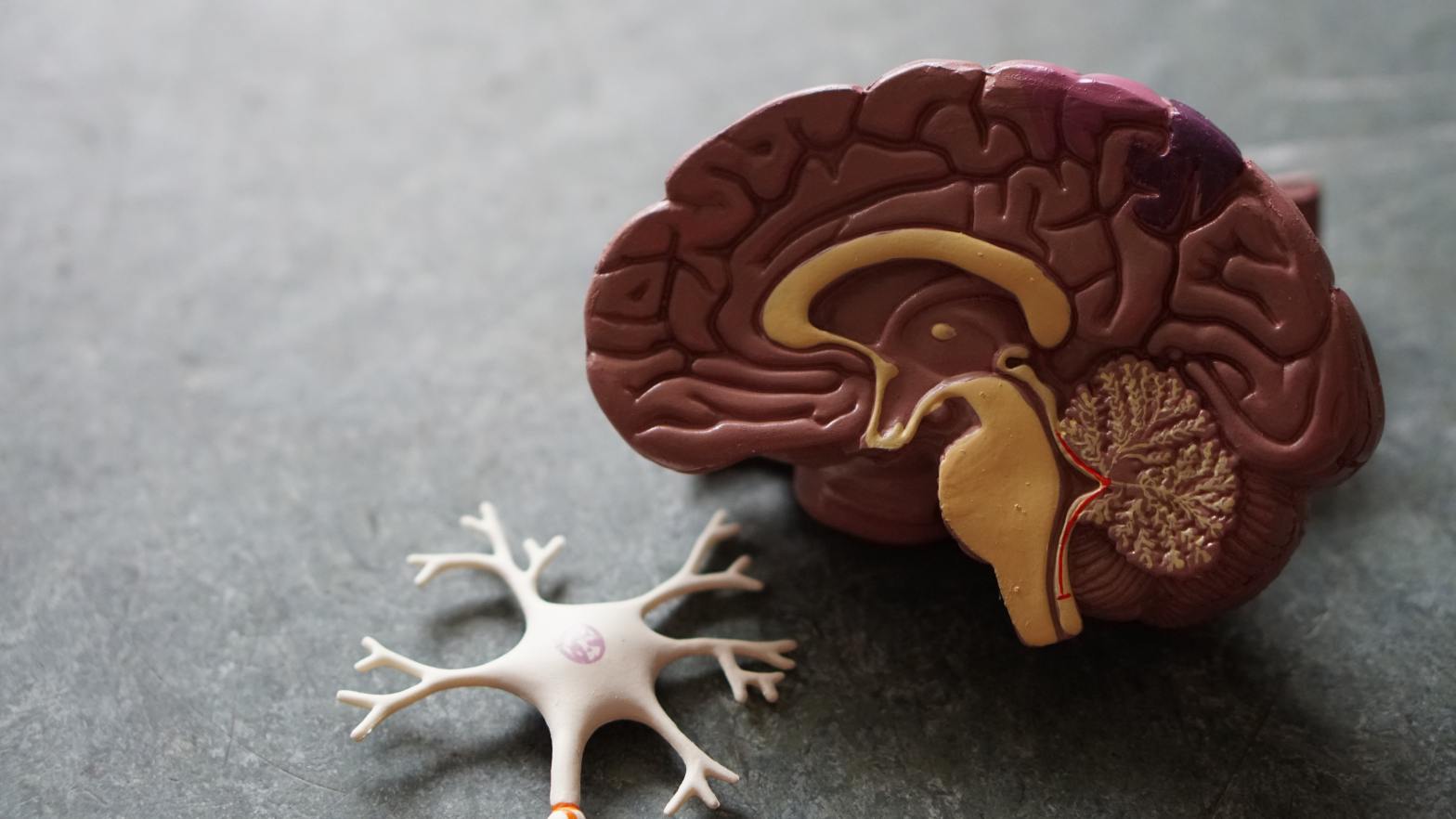

Sight words, or any word that a student has learned to read to the point of automaticity, can be phonetically regular or words with phonetically irregular parts. They can be long words or short words. They can be high-frequency or low frequency words. As long as the student no longer needs to sound the word out, but has seemingly automatic access to its pronunciation, we call the word a sight word, or a word that has been orthographically mapped, for that student. If the word is a sight word, the Visual-Word Form Area, or the brain’s letterbox, almost instantly connects the printed symbols on the page to pronunciation as well as meaning, if the student already knew the meaning of the word in spoken language.

All of the words on this blog are most likely sight words for you, if you did not need to sound them out, part by part. The phonemes (speech sounds) and graphemes (written letter(s) that represent each phoneme) are orthographically mapped, or inextricably linked in your memory system, and the letters on the page are then almost instantly connected to pronunciation and meaning. So how do we help students to become automatic word decoders, orthographically map words, and have seemingly instant access to large sight word bank?

In a recent discussion with Dr. Linnea Ehri, she wrote up and sent over a document with instructional guidelines that follow from her theory of orthographic mapping and research studies. She gave permission to share this with a wide audience of teachers and stakeholders in order to help increase understanding in the Science of Reading.

Below are Dr. Ehri’s guidelines for improving student sight word learning, or what is also commonly referred to as automatic word recognition, based on her theory of orthographic mapping and studies around reading (all emphasis/bolded words are hers). If you find it helpful, please be sure to share it with your colleagues.

Sight Word Learning Supported by Systematic Phonics Instruction

By Dr. Linnea Ehri

Written language is a human invention. It involves the representation of speech sounds with visual symbols. In English, an alphabetic language, there are approximately 44 unique speech sounds called phonemes. These are the smallest sounds forming spoken words. English phonemes are represented by the 26 letters of the alphabet, either individually or in combination. These alphabetic representations are called graphemes. It may seem confusing that there are 44 unique sounds and only 26 letters. This is possible because some sounds, such as /sh/, are represented by more than one letter. The word shop, for example, has three phonemes /š/ /o/ p/, and three graphemes <SH> <O> <P>.

Before children have acquired knowledge of letters and sounds, they may try to use visual memory for letter or word shape cues to try to remember how to read words. However, this approach is ineffective. Words do not have sufficiently distinctive letters or shapes for readers to be able to read thousands of them using visual memory. To accomplish this feat, they need to possess a powerful mnemonic (memory) system that acts like glue to retain all these spellings in memory so they can read words automatically and spell them accurately.

This mnemonic system entails two foundational skills that beginning readers need to acquire. One is phonemic awareness, the ability to segment spoken words into their smallest sounds or phonemes, and to blend phonemes to form recognizable words. The other is mastery of the major letter-sound (grapheme-phoneme) relationships comprising the writing system. These skills enable children to decode unfamiliar words by sounding out letters and blending their sounds to form words. This knowledge also enables children to store sight words in memory by forming connections between individual graphemes in the spellings of specific words and their respective phonemes in pronunciations, called orthographic mapping. Activation of these connections acts like glue to bond the spellings of words to their pronunciations in memory along with meanings. Once retained in memory, students can look at written words and immediately recognize their pronunciations and meanings. Reading words automatically enables readers to focus their attention on the meaning of the text they are reading while word recognition happens out of awareness. All words that are sufficiently practiced, not just high frequency words or irregularly spelled words, become sight words read from memory.

A comprehensive systematic phonics instructional program enables children to acquire the foundational skills needed to build a vocabulary of sight words in memory. It should include the following:

1. Grapheme-Phoneme Relations: Teaching children the major grapheme-phoneme (GP) relationships of the writing system guided by a scope and sequence chart that covers these relationships sequentially during the first year of reading instruction.

- This instruction can be facilitated by teaching GP relations using embedded picture mnemonics where the shapes of the letters resemble objects whose initial sounds are the phonemes represented by the graphemes (e.g., letter S drawn as a snake symbolizing /s/).

- Learning can be facilitated by teaching letter names that contain the relevant phonemes they symbolize in words (e.g., name of B contains /b/) and teaching children to detect these sounds in the names.

2. Phoneme Segmentation: Teaching children how to break spoken words into their smallest sounds or phonemes.

- Helping them detect these separate sounds by monitoring their mouth positions and movements as their articulators shift from one phoneme to the next in pronouncing words. Providing mirrors aid detection.

- Once they learn how to represent some phonemes with graphemes, teaching children to use these GPs to segment pronunciations containing those phonemes and represent them by writing letters or selecting letter tokens corresponding to the sequence of phonemes. This is an exercise in writing phonemic spellings, progressing from initial sounds, to initial and final sounds, to internal sounds in words, each taught to a mastery criterion.

- Once children know a small set of GP correspondences, such as a, m, s, p, f, o, t, they can begin to write phonemic spellings of many words (e.g., mat, pot, Sam, map, mop…).

3. Decoding: Once students know the constituent GP relations, teaching them to decode unfamiliar written words by sounding out graphemes and blending them to form meaningful words. This creates grapheme-phoneme connections to retain the words in memory for sight word reading.

- Begin with VC (vowel-consonant) words, then CVC words, each taught until mastery. Begin by teaching a small set of GPs to decode. Gradually teach additional GPs to include in words to decode.

- Begin with continuant consonants (i.e., s, m, n, f, l, r, v, w, y, z) that can be stretched and held. Teach students to decode by sounding out graphemes and blending them to form words without breaking the speech stream (e.g.,sssuuuunnn rather than ssss-uuuu-nnnn). Once learned, introduce words with stop consonants (i.e., b, d, g, j, k, p, t). The greater difficulty blending stops without breaks will be surmounted by prior practice with continuant consonants.

- For students who have learned the relevant GP relations, have them practice reading aloud lists of regularly spelled words containing many shared letters to a mastery criterion with corrective feedback (e.g., mat, bit, tab, tub, bet…). This forces students to process GP connections across all positions within words to read them. It promotes the spontaneous activation of GP connections to secure spellings in memory when words are read. It enhances knowledge of the spelling-sound writing system at the level of words.

- Once students have learned multi-letter spelling patterns such as syllables and morphemes, teach them to segment multisyllabic words into these subunits to decode them.

4. Spelling: Teaching children to analyze and remember the GP mappings between each grapheme in the spellings of specific words and its phoneme in the pronunciation to form connections and secure the words in memory for sight word reading and for writing correct spellings of words.

- One way to practice spellings of words in steps: 1. Students pronounce a word and count the phonemes they detect using sounds, mouth positions and movements. 2. Students view its spelling, match up its graphemes to the phonemes they detected, and reconcile any extra or unexpected letters (e.g., they are silent, part of a digraph). 3. The words are covered and students recall their analyses to write the words from memory.

- For irregularly spelled words, partial connections can be formed linking the regularly spelled graphemes and phonemes (e.g., S and D in said, all but the S in island).

- Once students learn multi-letter spelling-sound units, they can use these to form connections between spellings and pronunciations and store words in memory, for example, morphemic units (e.g., -ED, -TION, -MENT), and syllabic units (e.g., EX-CELL-ENT). This helps in learning multisyllabic words.

- Special spelling pronunciations can be created to enhance the mapping relationship between spellings and pronunciations to store words in memory (e.g., pronouncing chocolate as choc – o – late).

5. Pronouncing Words: Making sure that beginning readers read words aloud as they are reading text, particularly words that they haven’t read before. This enhances the likelihood that grapheme-phoneme connections are activated and spellings become bonded to pronunciations in memory for sight word learning compared to reading words silently.

6. Text Reading Practice: Providing plenty of practice reading text at an appropriate level of ease. This is essential for activating and connecting meanings to the spellings and pronunciations of sight words in memory, particularly words whose meanings are activated only when they are read in context (e.g., was, said, held, with).

I am very grateful for Dr. Ehri taking the time to write up these instructional guidelines and make them widely available to teachers and other stakeholders to help us better understand the science of teaching word recognition skills. I would highly recommend reading one of her latest pieces, The Science of Learning to Read Words: A Case for Systematic Phonics Instruction. In it, she describes many specific experimental studies testing conditions necessary for optimal word learning.

Another one of her publications, Orthographic Mapping in the Acquisition of Sight Word Reading, Spelling Memory, and Vocabulary Learning, has many more helpful explanations and a table that details the phases of word learning progress.

There are so many fun things to learn about how word-reading develops. Let’s keep learning more and more… and keep teaching well! If you have any feedback on these guidelines, Dr. Ehri would love to hear. Any comments left on this blog I will be sure she has access to as well!

Thanks so much for sharing this helpful guidance from Dr. Ehri on your blog! I’m curious to know her thoughts on two things. First, I noticed her use of the word *can* when she wrote, “Learning can be facilitated by teaching letter names that contain the relevant phonemes they symbolize in words (e.g., name of B contains /b/) and teaching children to detect these sounds in the names.” There is also a school of thought that teaching letter names alongside sounds can be confusing for some students. The common practice in synthetic phonics and linguistic phonics (based on Diane McGuinness’s prototype) commonly used in England is to avoid letter names and focus only on sounds at the very beginning of instruction. I’d love to know if she’s familiar with these programs/practices and if she agrees that while letter names *can* be helpful, they could also be confusing and might productively be avoided in initial reading instruction.

I’m also wondering about the necessity of the sequence of teaching children to isolate initial phonemes, then final, and then internal. I understand that there is evidence that this reflects a hierarchy of difficulty. However, there are programs and practices (again, used more commonly in England than in the US), that effectively teach children to isolate/segment and blend each phoneme in order, all through the word, and do not adhere to the initial-final-internal sequence. This seems to have the advantage of training children from the very beginning to attend to the full sequence of phonemes and move left to right while decoding and encoding words. I’d love to know of any research comparing these two approaches or any further thoughts on this.

Thanks again!

Miriam

LikeLike

From Dr. Ehri:

“Regarding teaching sounds and not letter names, most children already know letter names when they begin kindergarten to teaching names has already happened. Once they know names, it is much easier to draw sounds in the names they already know to teach them sounds. You should look at research by Theresa Roberts who has compared teaching letter names to letter sounds. She doesn’t really find any difference. You can email her and ask for her articles comparing letter name vs. letter sound learning. Her email is:

robertst@csus.edu“

LikeLike

About how letter names “can” help, they do help for children who learn the names easily (and usually come to school already knowing them). Some children, though, are indeed confused by having both and may not be fluent with oral spelling till they are even as old as nine. Children like this can spell with letter-cards and may even be able to write the letters before they name them. Of course, the letters h, q, w, and y are the hardest, along with having two sounds for c and g. I’ve found that spelling with letter-cards or visual cues works for these children. The teacher has to matter-of-factly name the letter as the child spells it, and the names start to emerge. As for beginning, then end, then middle, this sequence makes sense when testing. In my own research, out of 72 errors (made by 24 beginners), 2 were in endings, and the rest were in middles (vowels), which require extra ear training. On the other hand, If you use beginning-middle-end boxes for teaching words, you have to proceed from left to right.

LikeLike

Hi! Thanks for this. The readers I work with are middle-grade students who have mastered (mostly) mapping graphemes to phonemes in shorter, simpler, familiar words. They really struggle to read multi-syllable, unfamiliar words. Almost all of them read the first 1 or 2 syllables and then guess or just give up and end the word. I cannot be the only teacher trying to help kids with fragmented and incomplete decoding skills, but I can find very little curriculums, discussions, or materials to help these kids become skilled readers. What do you suggest?

LikeLike

From Dr. Ehri:

“You should look at the multisyllabic instruction we used to teach children to decode multisyllabic words. They pronounced the words, then segmented them by pronouncing each syllable while showing the spelling of this subunit in the word. They practiced repeating this strategy to read 100 words. Reference:

2004 Bhattacharya, A. & Ehri, L. Graphosyllabic analysis helps adolescent struggling readers read and spell words. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 37, 331-348.”

She added that she can email you a copy of the study if you cannot access. Just leave your email if so.

LikeLike

I would much appreciate a copy of this study. An unfortunate barrier to learning from research like Dr. Ehri’s is that we cannot easily access their essential work. Thank you so much for sharing.

-Bela Meghani

Learning Specialist

bela.meghani@ssfs.org

LikeLike

I agree! This is a great paper that would be very helpful if it were open access. Sent.

LikeLike

I find that, for children who muddle the middles of longer words, we need to follow two separate tracks: copious practice with the decoding of detached syllables (preferably through games) and copious practice with applying the rules of syllabication to nonsense words for the vc/cv, /cle, and v/cv words. (The vc/v and v/v rules need real words.) After a while, the two skills merge.

LikeLike

I am always harping about the wonderful Ehri, Deffner, and Wilce, 1984 study on embedded-picture letters because they speed up memorization and also make it unnecessary to use taps and tokens for phonemic-awareness training. When letters are easily recognized because they have been turned into familiar pictures, we can use actual letters (picture letters) for helping children segment the sounds in CVC words. I started using embedded pictures when I read about Curious George learning the alphabet in the 1960s and have made 39 packets of picture-letter cards to help children spell their way into learning how to blend sounds. (I’m sorry, but “cat” is in my first packet even though c is not a continuant.) Writing the words is the next step for teaching groups, but I use the packets for at-risk kindergarten children and practice writing on a parallel track. The tracks merge later. I also color-code my vowels–11 colors plus black and white, linked to colored key-word pictures. The ai in said is gray to match the picture of a gray elephant, so said is decoded like a three-letter-word. (I’ve found that color-match games work better than spelling packets for non-phonetic words.) Transition packets for a later phase use color-coded vowels (without embedded pictures) for words with vowel and consonant combinations, followed by black-and-white spelling with visual clues for quantities of one-syllable phonetic words, plus color-matching games for irregular words. I notice that Dr. Ehri works on a limited number of words for beginners. This is important because I’ve found that children need a chance to memorize their words, a few at a time, rather than practice sounding out without a chance to memorize. Sounding and memorizing are not mutually exclusive. Ann Coffeen Turner

LikeLike

Thank you for this informative piece! I was surprised to see CV words listed as the first for students to practice decoding. Are all vowel sounds being taught simultaneously? The OG approach in which I was trained has students begin with closed (or short) vowels only, so students gain a lot of practice with VC, CVC (and even CCVC, CVCC and CCVCC words) before introducing the open (aka long) vowels that are found in CV words.

LikeLike

From Dr. Ehri:

“This is a good point. I have revised my paper to incorporate. I have referred to decoding with short vowels and have deleted decoding CV.

Begin with a set of short-vowel vowel-consonant (VC) words (e.g., at, Ed, it, on, up), then sets of CVC words, each set taught to mastery. Decoding instruction can begin when children know only a limited number of grapheme-phoneme relations.”

LikeLike

Any advice on where to access games like that (or examples of games you make up)? If I understand you correctly, we should be breaking words into syllables, then syllables into sounds. When practicing breaking rules into syllables, why do you use nonsense words for some words and not others?

LikeLike

To Kathleen O’Connor: I have what I call “Trading Games.” 152 words of two and three syllables, nine words to a game. They come on print-and-cut pages. The approach is through decoding the separate syllables and then combining the two or three syllable cards to make a word. There are two directions. 1 – Like Tiffany Peltier’s Dr. Ehri quote: Pronounce the word, segment it, spell the segmented syllables. 2 – Like my Trading Games”: Decode the pre-segmented syllables, then combine the segments to make the word. Both approaches work–two roads to the same destination. About nonsense words: Some students, especially in middle school, have already memorized a number of polysyllabic words but don’t have a good decoding technique for unfamiliar words. These students do well with nonsense words for developing the necessary decoding technique. For real words, nonsense syllables combine to form real words. For nonsense words, real syllables combine to form nonsense words because each of my nonsense words have syllables that come from real words. Also, my games come with Dividing Pages of nonsense words for practicing the VC/CV, V/CV, and /CLE rules. (The VC/V and V/V rules have to be exemplified by real words.) The pages are presented as nonsense words so that the student will divide by rule and not by ear, If you already know the word, you no longer need to divide it. If it’s a nonsense word, you have to know and use the rule. I don’t ask children to read the nonsense word they’ve divided because reading is through the games. Children who have difficulty decoding often race through the rules and gain confidence with dividing while learning to improve their decoding through the games, thereby working on two parallel tracks. http://www.mnemonicpictures.com

LikeLike

Thank you Dr Ehri! I live in hope that articles such as those linked in the last few paragraphs will become readily available for all teachers.

LikeLike

I would also like a copy of Dr. Ehri’s research: 2004 Bhattacharya, A. & Ehri, L. Graphosyllabic analysis helps adolescent struggling readers read and spell words. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 37, 331-348.”

LikeLike

Great information to share with teachers and admin.

I was wondering why the syllabic units of excellent are EX-CELL-ENT and not EX-CEL-LENT. Are we looking at the morphemes to do the syllabication?

LikeLike

When the rules “argue” in words like ex cel lent versus ex cell ent, I find that younger children respond to (and need) the rules of syllabication at a younger age than students who are ready for structural analysis. I use the syllabication rules because they apply as well to words that can’t be easily analyzed through structural analysis. For older students who already know the word excellent and are ready for roots and affixes I put the whole word “excellent” (UNDIVIDED) on one card and the “cell” on another. By this time, they are ready to see how “the rules argue,” without being as indignant as younger children are when confronted by this kind of thing.

LikeLike

Fabiola,

Dr. Ehri mentioned the study by Bhattacharya and Ehri where students were taught to break multisyllabic words into syllables based on vowel nuclei. “We allowed either segmentation in the case of excellent as long as the division preserved the three separate vowels: ex-cell-ent, or ex-cel-lent. Morphemes were not considered in this study. So I would accept either division, although if students already know the spelling of “cell” it might be easier to remember the spelling of excellent by noting the presence of this smaller single-syllable word. Doubled letters are harder to remember so preserving them in one more memorable, known word syllable might boost memory for the full spelling of excellent.” -Dr. Ehri

LikeLike

Accepting both makes sense to me (both ex cel lent and ex cell ent). I’m making packs of cards for roots and affixes, and I’ve decided to have one card for the root and one card for the undivided word. This way, a child can see the root embedded in the whole word, thereby avoiding the “rules argue” issue. I’m not sure I’d do this with a child who hasn’t had plenty of practice with VCCV and VCV and with the detached syllables in my Trading Games.

LikeLike

I have learned so much reading this blog- my aha is the steps she lists in teaching- this will be a great guide for me as I share this with others. Having been in education for 30 years I have had many questions but have always stuck to what made the most sense to me and its great to see that my thinking is very similar to what I just read. Thank you!

LikeLike

I know this is a later question, but I am wondering about a specific area. I know that phonics should typically be taught prior to an application in decoding such as in guided reading, for K, 1 and 2. But as students move into 3rd grade, wouldn’t it make sense for the phonics direct instruction to be moved to within a writing block, where they are not only utilizing what they know about the sounds, but the actual etymology of the words?

LikeLike